Joseph Stiglitz’s influential call on the Greeks to vote ‘no’ in Sunday’s referendum has received attention from all corners of the globe. In this response, Kira Gartzou-Katsouyanni and Philip Schnattinger, critically analyse Stiglitz’s arguments and put forward an argument for a ‘yes’ vote.

Joseph Stiglitz’s call on the Greeks to vote ‘no’ in Sunday’s referendum has received broad international publicity and has given an enormous boost to the ‘no’ campaign in Greece. Yet many of his arguments about both economics and politics are at best one-sided.

Stiglitz talks a lot about the Eurozone’s democratic flaws. Indeed, many of us have participated in discussions about the European Union’s democratic deficit in the past, and there is no doubt that there are ways in which the Eurozone’s democratic credentials can be improved.

But the Eurogroup’s decision not to extend the economic adjustment programme beyond its expiry date was not an example of anti-democratic behaviour by European technocrats. On 20 February, the Greek government agreed to the extension of the programme which was due to expire on 30 June. It has been publically known for five months that without another agreement by the end of June, Europe’s money to Greece would run out. We all knew that this would include the end of the ECB’s emergency liquidity programme, which had already been increased in size several times to keep the Greek banking sector afloat.

Greece is not the only democratic nation in the Eurozone: the elected leaders of the other Eurozone countries were not able to simply disregard their own democratic procedures and extend Greece’s bailout programme without an agreement, and without the approval of their parliaments. If Tsipras wanted to have a referendum without the chaos of bankruptcy, financial meltdown and queues in banks, petrol stations, and supermarkets, he should have conducted this referendum a month ago. Supporting the myth that the ECB hasn’t increased the size of its emergency liquidity program in order to punish the Greek government for conducting a referendum, which is a myth that Alexis Tsipras shamelessly propagates to the Greek people, shows an unforgivable disregard of the facts surrounding last February’s agreement and a disdain towards the democratic processes of other member states.

Furthermore, any discussion about democracy in the context of this referendum must include a reference to the profoundly anti-democratic way in which the Greek government is conducting the referendum process. The Greek people are called, at one week’s notice, to vote ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to an incomprehensible question, about a draft proposal that is no longer on the table. This has led the Council of Europe to assert that the government’s conduct of the referendum process falls short of international guidelines. The ballot paper features the option of ‘no’ above that of ‘yes’, in order to remind people inside the voting booth of the government’s preferred option: an option that is favoured by a disgraceful coalition of Syriza, the far-right Independent Greeks, and the Nazi Golden Dawn.

In the meantime, the government is running a campaign of misinformation about the stakes of the referendum, denying that a ‘no’ vote will lead to the country’s exit from the Eurozone, despite clear statements to the contrary by most major European leaders. While stubbornly ignoring the facts, government members are bullying journalists who express their concerns about the Greek economy, and are employing a language of war, resistance, and nationalism against Greece’s European partners. If this dispute is ‘about power and democracy’, as Stiglitz claims, then Syriza is definitely not on democracy’s side.

Turning to the article’s economic arguments, Stiglitz correctly points out the degree of Greece’s suffering during the last five years. However, by blaming the crisis entirely on the troika, he fails to show an appreciation of the internal causes of the crisis and the political economy of recovery. For instance, Stiglitz overlooks the undisputable fact that with a deficit in double figures, Greece was in desperate need of an economic reform programme in 2010. This programme would have to include institutional and administrative modernisation reforms that Syriza has stubbornly opposed for years. Stiglitz depicts the situation as a typical example of the ‘austerity vs. Keynesianism’ debate, when the reality is far more complex.

Furthermore, beyond a vague reference to a future that may not be ‘as prosperous’ as the past, Stiglitz fails to spell out what the alternatives to the European rescue packages would have meant for the livelihoods of ordinary Greek people in 2010 or today. After an uncontrolled default and an exit from the Eurozone, Greece would plunge into chaos. The savings of Greek pensioners would vanish overnight; imports of medicine, fuel and other basic goods would become prohibitively expensive; the government, which will run a primary deficit, would be unable to pay salaries or operate hospitals and schools; and the real economy would collapse. As the Mayor of Athens said on Wednesday, ‘there is always something worse than a bad situation’. Simply repeating the numbers that reveal the economic hardship that Greek people have endured during this crisis is not a sufficient argument for the ‘no’ campaign. After all, the drachma may prove to be the most cruel type of austerity.

In order to avert such a catastrophe, Greece was lent funds in order to meet its financing needs and roll over existing loans. Since the aim of the economic adjustment programmes was to avoid the country’s uncontrolled default, it was never a surprise that most of the money went to Greece’s pre-crisis creditors, which were mostly banks, rather than going to the Greek people themselves. The economic adjustment programmes were never meant to be used as humanitarian aid: they aimed to sustain Greece’s credibility as a borrower, and they were successful in that, as shown by Greece’s return to financial markets in 2014. From this perspective, it is hard to understand Stiglitz’s dismay that most of the money from the rescue funds ‘has gone to pay out private-sector creditors’.

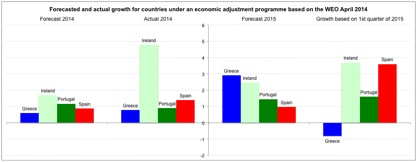

Surprisingly, Stiglitz doesn’t talk about the economic developments in Greece since Syriza came to power and steered the economy towards leaving the Eurozone. The graph below shows that actually the IMF forecasts predicted the growth rates in Eurozone countries quite accurately in 2014 (IMF WEO April 2014). In 2015, the predicted and actual growth rates were quite close for other Eurozone countries, but not for Greece. The reason for the mismatch in the Greek case is that the forecasts were made before Syriza came to power. The Syriza government created an atmosphere of uncertainty that caused an economy that had suffered an enormous blow in 2010, but that had become one of the fastest-growing economies of the Eurozone in the last quarter of 2014, to enter a new phase of depression. This depression will only deepen and become more painful if ‘no’ prevails on Sunday and Greece leaves the Eurozone.

Sources: IMF WEO April 2014 Eurostat , Central Bank of Ireland

Stiglitz’s article is a collection of economic and political half-truths. Should the ‘no’ campaign prevail and the Greek people be reduced to pauperisation for years to come, Stiglitz will bear a crushing responsibility.

Kira Gartzou-Katsouyanni and Philip Schnattinger are recent MA graduates in International Relations and International Economics from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

Note: The views expressed in this post are those of the authors, and not of the UCL European Institute, nor of UCL.

Photo by Robert Anasch on Unsplash

Leave a comment